-

On the hills of Jharkhand, water crisis renders life difficult in tribal villages

Women have to travel for miles to access this necessity, most of which is dirty, as water towers and hand pumps lie defunct.VAIBHAV VIVEK

Women have to travel for miles to access this necessity, most of which is dirty, as water towers and hand pumps lie defunct.VAIBHAV VIVEK

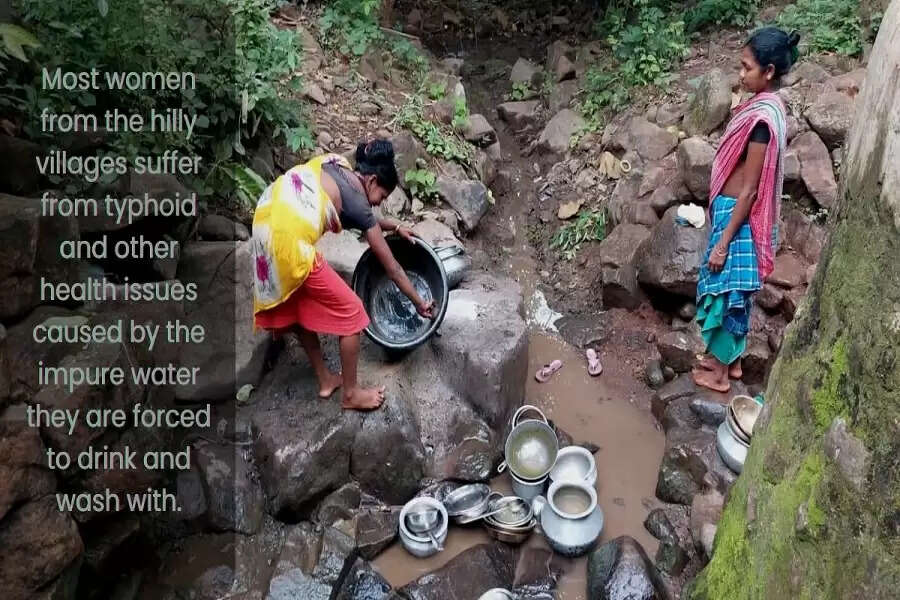

Godda, Jharkhand: Mesa Paharin of Tokadia Tola in Sundarpahari, in Jharkhand's Godda district, waits in a queue of women, a large plastic tub on her head filled to the brim with dirty utensils that need to be washed. The sole source of water for them is a small waterfall trickling down the mountains outside their village. About 30 women, who use this waterfall regularly, gather here since morning awaiting their turn for at least four hours every day.

“After struggling with water crisis for years, we are now used to it,” Mesa says, adding that the water tower that had been installed operated for only six months before the pump was stolen; it's been lying defunct since.

Sundarpahari in Godda district is a small community development block about 16km from the district headquarters. There are some 277 villages in this picturesque land surrounded by mountains and forests. The mountains are home to several highland tribes, whereas the plains and forests are inhabited by Santhals and other tribes. The total population of the block is about 65,000, and life here is rendered extremely difficult for this populace due to severe water scarcity.

Acute water crisis in the hills

A visit to the hilly villages of Tilbhita, Telodhuni, Palamdumer, Belmako Bhuski, Goga, Gamharo, Pakeri and Gosmara reveals the extent of the water deficit in the region. Speaking to 101Reporters, local villagers say their biggest struggle is procuring water for their daily use.

District Mineral Foundation (DMF) Trusts have been developed across most mining districts in India over the past five years, since the amendment of the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act (MMDR) in 2015. These district-level bodies work in the interest of mining-affected people and areas, based on the fundamental idea that local communities have the right to benefit from natural resources extracted from their area.

According to a report published by the Centre for Science and Environment, Jharkhand has allotted the highest amount to drinking water supply projects (primarily piped water supply works), which account for nearly 77% of the state's total DMF allocation. However, in a report by the trust in Godda, which shows the expenditure on drinking water projects, only five villages of Boarijor block find mention, with Sundarpahari being left out.

Under the state government’s scheme to develop primitive tribal groups (PTG), solar-powered water towers were set up in the hilly regions. However, most of these now lie inoperative, due to the solar panel-operated pumps being stolen or faulty boring works. These towers were installed in both Telodhuni and Palamdumer. However, the pump was stolen from one of the towers, while the other stopped functioning after the solar panel was damaged in a storm.

“Both the towers stopped functioning more than a year ago. We contacted the officers responsible, but they have yet to take any initiative,” says Deva Paharia, the village pradhan.

The solar-powered water tower in Belmako Bhuski village operated for hardly two months, before malfunctioning due to faulty boring works, claim villagers. Their repeated complaints fell on deaf ears, and many allege they are being ignored because the government doesn’t care about the tribal people.

The onus of water supply falls on women

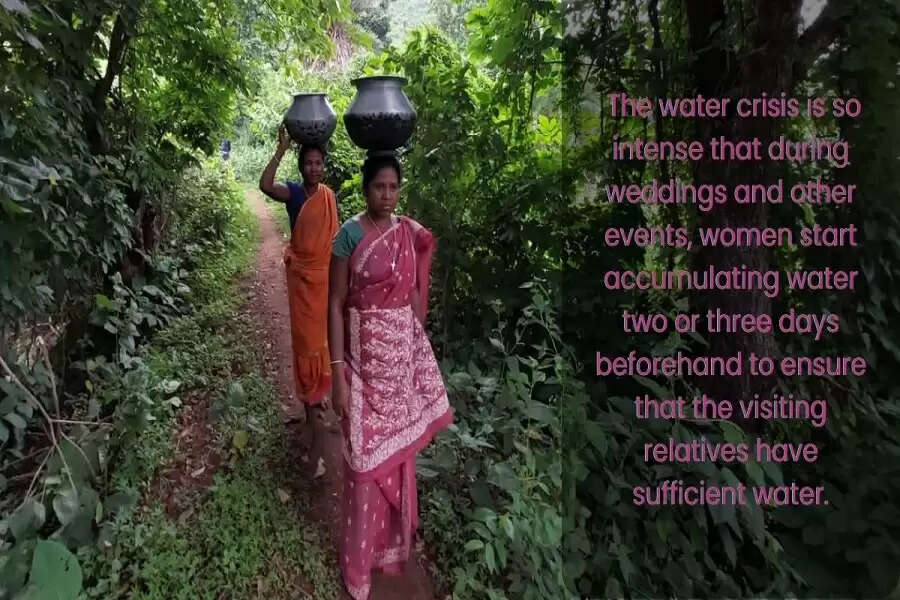

Generally, the women are responsible for fetching water for the entire household. Marta Paharin of Tilbhita says she has to travel to the small well located 500m from her village at least 10 times each day, lugging multiple vessels with her. Each time she has to spend 45 to 50 minutes awaiting her turn, which delays her other household chores and causes disaffection within the family.

Elderly women like Bamdi Paharin find it even harder to continue with this routine. Bamdi says she has to travel down hilly tracts to reach the waterfall that's the sole source of water in her village. The few months when the solar-powered tower functioned, they had found some respite, but now they were back to the same predicament. It becomes even more dangerous during the monsoon, when the hilly roads are slippery, and there’s a high risk of accidents.

Lily Malto of Palamdumer, who was married into a family in a different village, says there’s no water crisis at her in-laws’ place because the government installed two hand pumps there. However, in Paladumer and other hilly areas, the water crisis is so intense that during weddings and other events, women start accumulating water two or three days beforehand to ensure that the visiting relatives have sufficient water.

Local authorities promise action soon

Sundarpahari block falls under the Barhet assembly constituency — the seat of Hemant Soren, the sitting MLA from the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha and also the chief minister. On December 14, 2020, he had met with officials of the drinking water and sanitation department and issued orders to ensure water supply to every tribal household. He had also instructed for the process to be videographed to confirm the progress of work. This order, however, has not been implemented till date.

Block Development Officer Vijay Prakash Marandi says a few days ago, the department had been instructed to repair the defunct water towers and hand pumps and attempt to resolve the water crisis by taking feedback from villagers and village heads.

Rameshwar Gupta, executive engineer, drinking water and sanitation division, Godda, says that in 2019-20, work was undertaken under the PTG scheme to ensure drinking water supply in tribal lands. A solar water tower was also constructed. However, no schemes under the DMF funding is currently running in any of these villages.

Reena Soren, chief of Karmatad panchayat, says she was only recently elected but was aware of the water crisis.

“Even though a panchayat chief doesn’t have much funds to disburse, I shall try to dig up small wells and fill them with rainwater to alleviate the crisis,” she asserts.

Urmila Hembram, former panchayat chief, says it's of utmost importance to educate the masses and make them aware of their rights, so they can appeal to the government directly and make their grievances heard.

Retired basic health worker Bhim Marandi says the residents of the tribal villages in the hilly regions are susceptible to diseases like jaundice and typhoid due to lack of access to clean water. Women in these villages also suffer from chronic weakness and other ailments due to back-breaking labour.

Salomi Hembram, an auxiliary nursing midwife at a community health centre in Sundarpahari, says most women from the hilly villages suffer from typhoid and other health issues caused by the impure water they are forced to drink and wash with.

Edited by Rashmi Guha Ray(The author is a Godda-based freelance journalist and a member of 101Reporters, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.)